£100 million money laundering conviction: Lessons for accountants

In 2022, Emirati national Abdulla Alfalasi was jailed for nine years, following a conviction for leading the biggest...

READ MORE

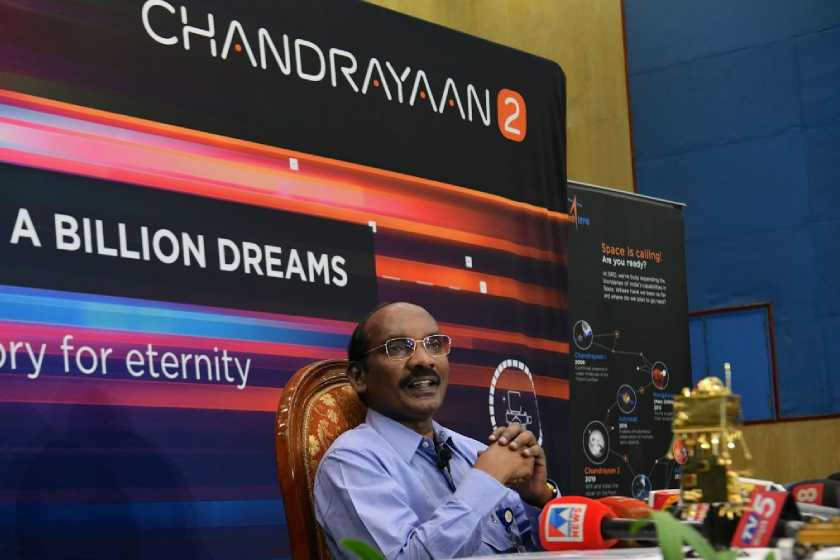

From the early days of human space activity in the 1960s, missions to the Moon have attracted significant global attention. India’s recent success in landing the Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft on the Moon was technically demanding and occurred in a previously unexplored part of the Moon.

As well as the scientific benefits, India has already enjoyed the significant attention that still accompanies high profile space missions, gaining news coverage across the globe.

There are always considerable demands upon government spending. So why do some countries continue to put substantial resources into space activity? And does this type of success produce tangible national and international benefits beyond a few days in the media spotlight?

Though it sounds inordinately expensive to outsiders, getting a nation into space is no longer necessarily as costly as it used to be. Access to space is getting cheaper, especially for nations who have access to their own launch vehicles.

This is illustrated by the relatively low cost of the Chandrayaan-3 mission. Initially, the budget was a relatively modest US$70m (£55m). Although the final cost has not publicly disclosed, it is believed to rival the lowest cost lunar lander missions currently under development in the US.

Lowering the cost of space missions has meant a dramatic increase in the number of countries looking to have a presence in space. India has now produced at least 140 commercial space companies registered with the Indian Ministry of Corporate Affairs, that, between them, have attracted US$120 million in investment at a rate that is doubling on an annual basis.

The US Apollo programme has shown that space exploration can drive technological innovation. These innovations have applications in various industries including telecommunications, remote sensing and the creation of new, useful materials.

The success of Chandrayaan-3 will bring more of the high-skilled jobs that every economy – developed and developing – depends on for further growth. In addition to those scientific and technical workers, support and administrative roles will also be created.

The development of a space industry within a country can have significant benefits to growing the economy, beyond the money initially invested. Along with the scientific discoveries that Chanrayaan-3 may make, these are obvious benefits for any nation looking to showcase itself on the global stage.

Working as a member of the global scientific community enables countries to use space exploration as a way to foster closer ties. As part of this, there can be a pooling of expertise as well as technology transfer programmes, which lead to applications moving from space tech to other parts of society, such as fire-retardant clothing being used in other industries.

It is possible for deeper diplomatic and economic relations to emerge from these bespoke scientific and technical arrangements. India already has close collaborative ties with the US.

The success of the Chandrayaan-3 mission will not only help develop these ties but will help illustrate the value of India signing the Artemis Accords, an agreement fostering international cooperation to expand space exploration to Mars, and becoming a fully-fledged partner in the US programme to establish a permanent human presence on the Moon.

Given that Russia had tried and failed to land the probe, Luna 25, on the Moon a few days earlier, India’s success was significant. The Russian failure has been viewed as an indication of its decline as a space power. It is prudent for ambitious governments with an eye on space to remember that prestige can cut both ways.

The national security dimension of space activity cannot be ignored. If, as the adage goes, “all politics is local politics” then the achievement of India in space will not have been lost on its neighbours, Pakistan and China. China, the dominant superpower in the region, will see it as competition to its own lunar programme and space ambitions.

More broadly, it will also recognise the threat posed by closer Indian relations with the US. That success in space could seem threatening to India’s neighbours. Such an advantage carries the implicit warning that such technology could also be used for military and defence purposes in future.

It was fortuitous for India’s prime minister Narendra Modi that the space landing was announced while he was at the Brics summit of fast-growing economies. The perception that under his leadership India is standing on the world stage because of its scientific and technical prowess will also play well domestically.

Yet, the boost to Indian prestige and confidence brought about by the success of the Chandrayaan-3 mission is ultimately more than an attempt by an ambitious nation trying to gain a place on the world stage. India already has the attention of the world and is seen by many as a crucial counterbalance by the US to the threat posed by China. Ultimately, this was a mission of scientific exploration, built on sustainable economic foundations.

Space exploration in the 2020s is dramatically different to that of the first lunar space race between the US and the Soviet Union. Nonetheless, the international prestige that a successful lunar programme can bring is still a very attractive option for governments who are looking to boost their image both domestically and internationally, as well as providing an economic lift.![]()

Christopher Newman, Professor of Space Law and Policy, Northumbria University, Newcastle

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.