£100 million money laundering conviction: Lessons for accountants

In 2022, Emirati national Abdulla Alfalasi was jailed for nine years, following a conviction for leading the biggest...

READ MORE

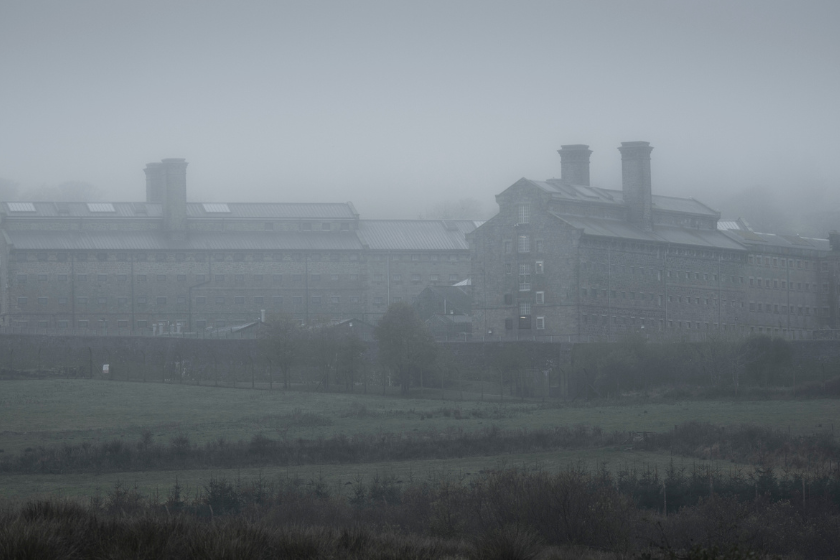

The UK’s long-standing problem with prisons operating beyond their capacity is only set to worsen. Here’s why that matters, what’s causing the problem, and steps that could solve it.

In January 2019, almost five years ago, The Guardian published a long interview with then-prisons minister Rory Stewart under the headline Rory Stewart: ‘I’ll resign if prison violence doesn’t improve’.

The Conservative Party minister detailed shocking statistics about violence in prisons: Among the 82,500 prisoners in England and Wales, in 2018, there were around 50,000 self-harm incidents and more than 32,500 assaults, including 10,000 against staff. There were at least 87 suicides, five murders and more than 300 deaths from ill-health or natural causes.

“By any measure, our prisons are in a state of crisis,” the article said.

In the five years since, there has been little improvement – by most measures the situation is now worse.

The total prison population of England and Wales has now risen to 85,851.

The government’s Safety in custody summary tables report that in the 12 months to June 2023, 64,348 self harm incidents were recorded – that’s 778 per 1,000 prisoners – with more than 44,000 instances of self-harm in male prisons and more than 20,000 in female prisons.

Assault incidents were down to 23,557, but total deaths were still over 300, including three murders and 92 suicides.

Why should the general public care what happens behind the walls of prisons? Partly, because everyone’s tax pounds are spent on prisons with an express purpose. In the words of HM Prison Service: “We keep those sentenced to prison in custody, helping them lead law-abiding and useful lives, both while they are in prison and after they are released”. If that is not happening, it raises questions around the effectiveness of public spending.

But overwhelmingly, this matters because it affects the society we are a part of, and it affects all of us whether or not we interact with the prison system.

“Overcrowding and staff shortages mean prisoners have less access to training and support programs designed to reduce reoffending,” explains Nick Davies, Program Director at the Institute for Government and co-author of Performance Tracker 2023: Prisons. “Since 2009/10 there has been an 88 per cent fall in the number of prisoners starting these programmes. The inevitable result will be higher levels of reoffending.”

The Performance Tracker says the prison service is now in crisis, and the problem is accelerating. Since 2021, it says, the prison population has been “increasing at a rapid rate that is becoming increasingly unsustainable”.

The Ministry of Justice expects prisoner numbers to continue to increase at three times the rate of prison capacity.

Why is the problem of overcrowding so difficult to solve?

“There is a fundamental mismatch between supply and demand in the prisons system,” Davies says. “The government has increased demand by lengthening sentences, but has been unable to build enough new prison places.”

“Building lots of additional prison capacity is challenging because new projects often get delayed for years or stopped by opposition from local residents, who tend not to want large, new prisons opening in their area.”

Lengthening sentences are contributing to the problem of capacity, but short sentences are not without their impact either. Lower-level offenders are sometimes in prison for a week or less. Rory Stewart cited an average stay of 10 days at HMP Durham back in that 2019 interview.

“What is a prison supposed to do with someone in 10 days?” Stewart said.

“I’ve no doubt that the wrong kind of short sentence can damage the individual and ultimately damage the public because it can lead to more reoffending,” he said, adding that it was “long enough to damage the person and not long enough to change their life”.

In Scotland there has been legislation against sentences shorter than 12 months. But in England and Wales, it’s still being discussed.

In fact, Davies says, it has been discussed for a very long time. Over the past 13 years there have been a number of proposals to reduce the use of short sentences, but each has ultimately failed.

This is despite the fact that there is plenty of evidence to say that short sentences are highly ineffective when it comes to preventing reoffending. The prevention of reoffending, of course, is the desired outcome of a custodial sentence.

“These have generally been blocked by the Prime Minister for political reasons,” he says.

“Government has indicated it would like to reduce the use of short sentences, and could reform sentencing more substantially. But it wants to be seen as taking a tough line on law and order issues in the run up to the election.

“The King’s Speech stated that the government would legislate to introduce a presumption that sentences of less than a year would be suspended, but whether this ever makes it onto the statute book remains to be seen.”

Davies’ Performance Tracker identified a mismatch between prisoners and guards, with too many prisoners for both prison capacity and the number of guards.

“The overall number of operational prison officers increased by 1.3 per cent in 2022/23, though this still leaves total staff levels 10 per cent below 2009/10,” the report said. “This means the number of prisoners per operational staff member has increased to 3.8 in June 2023, from an estimated 3.5 in June 2010.”

Poor retention levels of prison officers leads to numerous other problems, Davies says. Fewer staff and less experienced staff means the physical space of a prison is not used as it could be, as prisoner management suffers. Inexperience also leads to an inability to manage difficult situations and to build relationships of trust with prisoners.

For these and other reasons, 42 per cent of male prisoners and 36 per cent of female prisoners now spend less than two hours each day out of their cells.

There is less access to rehabilitative services and activities and less effective care for prisoners who need it, leading to record levels of self-harm. In Q1 2023 alone, the Performance Tracker said, there were 1,683 incidents of self-harm per 1,000 female prisoners.

The solution may not be simple – but it could start with clear communication of the problem to the electorate, a dramatic increase in spending on prison infrastructure, a reduction in the use of short sentences and brave politics.